The death of a luger has landed the Vancouver Games at the centre of an international controversy, as questions mount about the safety of the world's fastest track and the official response to the tragedy.

Officials from the International Olympic Committee, Vancouver Organizing Committee and International Luge Federation all pinned the death of 21-year-old Georgian Nodar Kumaritashvili on mistakes he made coming out of the second-to-last curve on the run, and insisted that the track is safe.

That explanation triggered outrage from around the world, as luge officials from the United States and elsewhere raised questions about the track's speed - a concern that had been raised by some before Friday's accident - and access to the course for training runs.

Even if Mr. Kumaritashvili came out of curve 15 too late and couldn't regain control of his sled - his speed was 144 km/h - that doesn't explain his death, Georgia's President, Mikheil Saakashvili, said at a news conference. "I've heard remarks from the international federation [of luge] that what happened [Friday] was because of human error," he said.

"I don't claim to know the technical details, but one thing that I know for sure is that no sports mistake is supposed to lead to a death."

In luge, such accidents are rare - pointing to the need for a better explanation, Ron Rossi, chief executive of USA Luge, told reporters at the Whistler Sliding Centre Saturday.

"Lots of drivers make errors, but they don't come flying out of the track," Mr. Rossi said.

Track design and access to the track for training should all be scrutinized, he said.

"They need to be asking questions about lack of training time. Lack of track-designer accountability. I'm going to propose a rule change, to fine the track designers when things like this happen. I'm going to propose rule changes so there is more training time for all."

Canadian officials insist that all teams were given opportunities for practice, despite some accusations from abroad that they restricted access to the track.

"We worked very closely with the FIL [luge federation] ... And largely we've lived up to those obligations and surpassed them," said VANOC vice-president of sports Tim Gayda.

In addition to two international training weeks for the luge federation, "we also offered additional training for the smaller nations starting on Jan. 1 leading up to the Games," Mr. Gayda said. "So it's really up to the teams to take advantage of these training [dates]."

Mr. Kumaritashvili, who was ranked 55th out of 62 sliders in the world last year and had moved up to 44th this season, did 20 runs on the course in November, and another five this week before his last run Friday, said Svein Romstad, secretary-general of the International Luge Federation.

Mr. Romstad said he had no complaints about the amount of training time given to international teams.

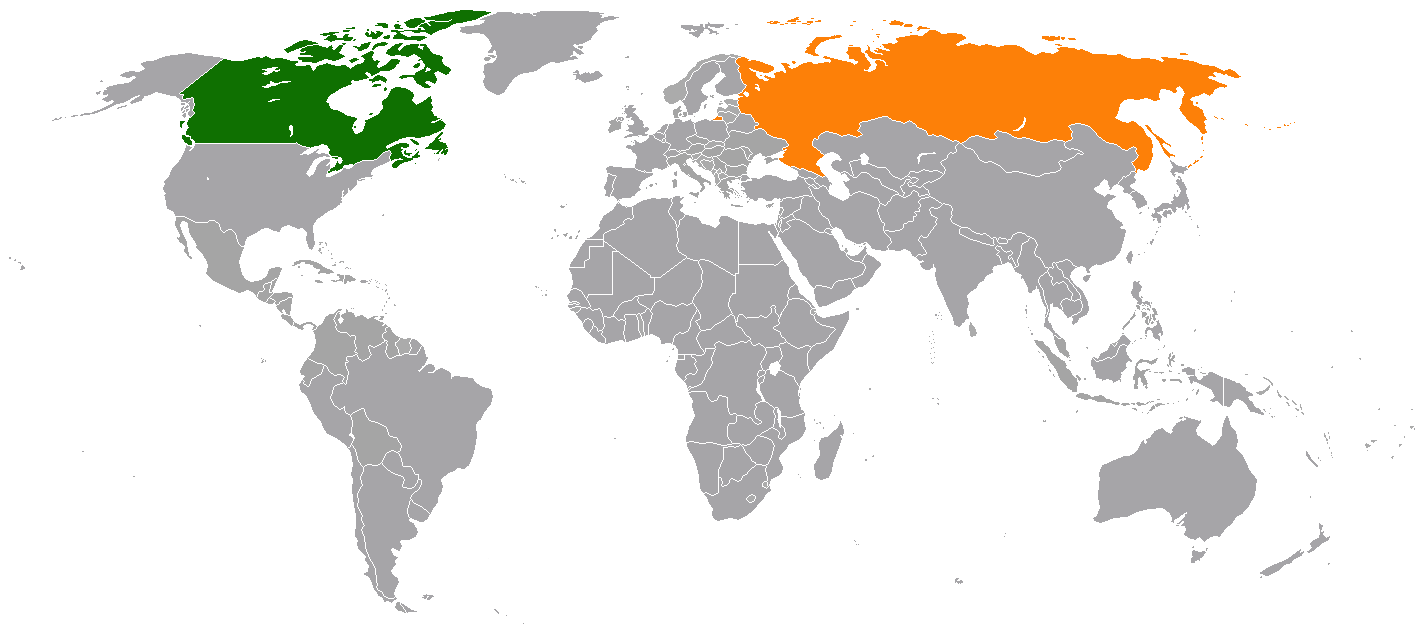

Mr. Saakashvili dismissed suggestions that Mr. Kumaritashvili lacked the experience to tackle such a difficult track. Mr. Kumaritashvili's father and uncle, he said, participated in luge; the family is from a part of the country that used to be a major winter sports training centre during Soviet times.

"You cannot say that it was inexperience," the Georgian leader said. "He is not coming out of the blue." He added that other more experienced athletes had had trouble with the track.

Training was a particularly crucial issue because of the track's speed. Its status as the fastest in the world, with a maximum speed of 155 km/h, had stirred concerns in the weeks leading up to the Games, as some experienced lugers questioned its safety.

Before the Olympics, American luger Tony Benshoof told NBC that when he first got on the track, "I thought that somebody was going to kill themselves."

A few weeks ago, the head of the International Luge Federation, Josef Fendt, told a British newspaper that the track in the $100-million Whistler Sliding Centre was too fast.

"We had planned it to be a maximum of 137 kilometres per hour but it is about 20 km/h faster," Mr. Fendt said. "We think this is a planning mistake."

Saturday, Mr. Fendt backed away from those comments, saying he was referring to future tracks when he said the track should have a maximum speed of 137 km/h.

"We're not saying the track is too fast," he told reporters. "I never said that the track is unsafe."

Mr. Fendt joined the chorus of officials who pinned the crash on Mr. Kumaritashvili losing control of his sled.

VANOC produced figures Saturday showing that out of more than 30,000 runs over the past two years, including luge, bobsleigh and skeleton, there had been only 350 sled turnovers. The "crash ratio," luge officials insisted, was no higher than other tracks.

Officials saw nothing out of the ordinary before Mr. Kumaritashvili's run. "When you look at the overall, for lack of a better word, crash ratio, it is on par with other tracks," said the luge federation's Mr. Romstad.

While they insisted the accident was not related to any "deficiencies" in the track's design, officials raised the wall of the track yesterday near turn 16 and moved the start of the men's competition to the women's starting position.

They also made changes to the ice surface to help ensure that when a sled veers off the track, it will be pulled back on. As for padding or hay bales around the steel poles, VANOC's Mr. Gayda said the objective is always to keep a slider on the track because once he or she flies off, padding or hay bales won't help to cushion an impact at such high speed. However, padding was added to the poles later in the day.

Wolfgang Staudinger, Canadian luge coach, said coaches were not consulted enough before the final decision was made to lower the start. He didn't know, he said, until he showed up in the morning and was handed a piece of paper.

"The people that are racing - the international luge and bobsled and skeleton communities - nobody will point fingers. This could have happened anywhere in the world. It's just a sad story that it happened here during training for the Olympics."

Mr. Romstad said officials considered halting the competition altogether, but decided to press ahead after meeting with team representatives.

He acknowledged that the new starting positions will only slow the men down by about 10 km/h. Instead, he said the changes were more about trying to calm the athletes.

"The bottom line is that the decisions made are to deal with the emotional components for the athletes, to mediate as best as possible the traumatic experience of this tragic event," he said.

Mr. Benshoof, the American luger who warned of the track's danger before the Olympics, was the first man to slide down the track after Mr. Kumaritashvili's death.

Mr. Benshoof said Friday he did his best to concentrate on his run.

"In my mind, I had two runs for a big competition. I'm treating it the same way. We have a job to do. I tried to put that out of my head."

CTV reports from Doug Saunders